Entrada destacada

lunes, 29 de diciembre de 2014

RELIGION AND CULTURE MATTER

What the world values, in one chart

VOX

The more globalized our world becomes, the more we learn about similarities and differences that cut across all cultures.

These things are sometimes easy to trace on a small scale. For instance, it's easy to chart the religious differences between, say, Indonesia and China. In 2000, 98 percent of Indonesians said religion was important to them compared to just 3 percent of Chinese citizens who said the same thing, according to WVS. But not every cultural comparison is that easy to make.

Two professors, however, are finding ways to compare how our values differ on a global scale.

Using data from the World Values Survey (WVS), professors Ronald Inglehart of the University of Michigan and Christian Welzel of Germany's Luephana University comprised this amazing Cultural Map of the World.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2886428/image.0.png)

The Ingelhart-Welzel Cultural Map of the World. (NB: the green cluster in the center of the map is unmarked, but is labeled South Asian.)

What you're seeing is a scatter plot charting how values compare across nine different clusters (English-speaking, Catholic Europe, Islamic, etc.). The y-axis tracks traditional values, versus secular-rational values.

What do those terms mean? According to WVS, traditional values (the bottom of the y-axis) emphasize religion, traditional family values, parent-child ties, and nationalism. Those with these values tend to reject abortion, euthanasia, and divorce. On the other hand, those with secular rational values (the top of the y-axis) place less preference on religion and traditional authority, and are more accepting of abortion and divorce.

The x-axis tracks survival values versus self-expression values. Survival values emphasize economic and physical security and are linked with ethnocentrism and low levels of tolerance. Self-expression values, according to WVS, "give high priority to environmental protection, growing tolerance of foreigners, gays and lesbians and gender equality, and rising demands for participation in decision-making in economic and political life."

WVS offers this admittedly simplified analysis of the plot:

... following an increase in standards of living, and a transit from development country via industrialization to post-industrial knowledge society, a country tends to move diagonally in the direction from lower-left corner (poor) to upper-right corner (rich), indicating a transit in both dimensions.However, the attitudes among the population are also highly correlated with the philosophical, political and religious ideas that have been dominating in the country. Secular-rational values and materialism were formulated by philosophers and the left-wing politics side in the French revolution, and can consequenlty be observed especially in countries with a long history of social democratic or socialistic policy, and in countries where a large portion of the population have studied philisophy and science at universities. Survival values are characteristic for eastern-world countries and self-expression values for western-world countries. In a liberal post-industrial economy, an increasing share of the population has grown up taking survival and freedom of thought for granted, resulting in that self-expression is highly valued.

The map, known as the Inglehart-Welzel map, was published in 2010, and was based on data published by the WVS between 1995 and 2009. The WVS "is the largest non-commercial, cross-national, time series investigation of human beliefs and values ever executed," according to its website. It's been around since 1981 and has surveyed over 400,000 respondents in more than 100 countries.

HOW DO YOU EVALUATE OBAMA?

5 WORST U.S. PRESIDENTS OF ALL TIME

by Robert W. Merry

THE NATIONAL INTEREST,

November 5.

In the spring of 2006, midway through George W. Bush’s second presidential term, Princeton historian Sean Wilentz published a piece in Rolling Stone that posed a provocative question: Was Bush the worst president ever? He said the best-case scenario for Bush was "colossal historical disgrace’’ and added: "Many historians are now wondering whether Bush, in fact, will be remembered as the very worst president in all of American history."

The Wilentz assessment was probably a bit premature. It is difficult to judge any president’s historical standing while he still sits in the Oval Office, when political passions of the day are swirling around him with such intensity. And yet the Founding Fathers, in creating our system of government, invited all of us to assess our elected leaders on an ongoing basis, and so interim judgments are fair game, however harsh or favorable.

Which raises a question for today: How will Barack Obama be viewed in history? Will he be among the greats? Or will he fall into the category of faltering failures?

Before we delve into that question, perhaps some discussion would be in order on what in fact constitutes presidential failure and how we arrive at historical assessments of it. First, consider the difference between failure of omission and failure of commission. The first is when a president fails to deal with a crisis thrust upon him by events beyond his control. James Buchanan, Abraham Lincoln’s predecessor, comes to mind. He didn’t create the slavery crisis that threatened to engulf the nation. Yet he proved incapable of dealing with it in any effective way. In part this was because he was a man who lacked character and hence couldn’t get beyond his own narrow political interests as the country he was charged with leading slipped ever deeper into crisis. And in part this was simply because he lacked the tools to grapple effectively with such a massive threat to the nation.

But, whatever the underlying contributors to his failure, there is no denying that his was a failed presidency. It was a failure of omission.

A failure of commission is when a president actually generates the crisis through his own wrong-headed actions. That could describe Woodrow Wilson in his second term, from 1917 to 1921. He not only manipulated neutrality policies to get the United States into World War I but he then used the war as an excuse to transform American society in ways that proved highly deleterious. He nationalized the telegraph, telephone and railroad industries, along with the distribution of coal. The government undertook the direct construction of merchant ships and bought and sold farm goods. A military draft was instituted. Individual and corporate income tax rates surged. Dissent was suppressed by the notorious Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, who vigorously prosecuted opposition voices under severe new laws.

(You Might Also Like: 6 Best U.S. Presidents of All Time)

One result from many of these policies was that the economy flipped out of control. Inflation surged into double-digit territory. Gross Domestic Product plummeted nearly 6.5 percent in two years. Racial and labor riots spread across the land. The American people responded with a harsh electoral judgment, rejecting Wilson’s Democratic Party at the next election and giving Warren G. Harding, hardly a distinguished personage, fully 60.3 percent of the popular vote. In addition, Republicans picked up sixty-three House seats and eleven in the Senate. The country has seen few political repudiations of such magnitude.

That’s failure of commission. Although historians have given Wilson a far higher ranking in academic polls than he would seem to deserve, it’s difficult to argue with the collective electorate when it delivers such a harsh judgment. If we assume that our system works, then the electoral assessment must be credited with at least some degree of seriousness.

Getting back to George W. Bush, his foreign policy would almost have to be considered a failure, and it was a failure of commission. He wasn’t responsible for the 9/11 attack in any meaningful way, of course, but his response—sending the U.S. military into the lands of Islam with the mission of remaking Islamic societies in the image of Western democracy—was delusional and doomed. One need only read today’s headlines, with forces aligned with Al Qaeda taking over significant swaths of territory within Iraq, to see Bush’s failure in stark relief.

In addition, Bush’s wars sapped resources and threw the nation’s budget into deficit. The president made no effort to inject fiscal austerity into governmental operations, eschewing his primary weapon of budgetary discipline, the veto pen. The national debt shot up, and economic growth began a steady decline, culminating in negative growth in the 2008 campaign year. The devastating financial crisis erupted on his watch.

It’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that Bush belongs in the category of the country’s five worst presidents, along with such perennial bottom-dwellers, in the academic polls, as Buchanan, Franklin Pierce and Millard Fillmore. Harding also occupies that territory in these polls, but it’s difficult to credit such an assessment, given that he quickly dealt successfully with all the problems bequeathed to him by Wilson and presided over robust economic growth and relative societal stability.

Thus do we come to one man’s assessment (mine) of the five worst presidents of our heritage (in ascending order): Buchanan, Pierce, Wilson, G. W. Bush and Fillmore.

Is it conceivable that Obama could descend to such a reputational depth? It depends, in large measure, on the outcome of the effort to salvage and bolster the president’s profoundly troubled Affordable Care Act. There’s no doubt that, in domestic policy, the Obama presidency will be defined by that single issue. And, if it destabilizes the nation’s health-care system and the overall economy to the extent that some are predicting, the president’s historical reputation will be severely affected. And this failure, if it emerges, will be viewed as one of commission, not of omission.

On the other hand, if the Obamacare system is righted and the country ultimately manages to transition smoothly into a new health-care era, the president’s historical reputation will be salvaged. As it appears now, absent some powerful new development in American politics (which never can be ruled out), Obama’s historical standing will rise or fall with Obamacare.

But one thing we know: Neither the judgment of history nor the judgment of the electorate will be rendered with any degree of sentiment or sympathy. As Lincoln said, "Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history. We…will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significance, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation."

Robert W. Merry is political editor of The National Interest and the author of books on American history and foreign policy. His most recent book is Where They Stand: The American Presidents in the Eyes of Voters and Historians.

Image: White House/Flickr.

Editor's Note: This piece was posted in January and is being reposted due to popular interest.

SYRIZA FAVORITO EN ELECCIONES GRIEGAS DEL 25 DE ENERO

teóricamente era sólo un trámite parlamentario, la elección de presidente de Grecia, se ha convertido en el mayor cataclismo políticovivido en el país desde el inicio de la crisis económica, tras dos intentos fallidos previos para elegir al jefe del Estado que han atizado la inestabilidad y los temores de Bruselas y la troika y que este lunes han conducido definitivamente al país a las urnas, en convocatoria anticipada, al concluir la elección presidencial sin resultado. Las encuestas pronostican que la izquierdista Syriza ganará esos comicios, que serán el 25 de enero.

Al Ejecutivo de Samarás le resultó por tanto imposible granjearse más apoyos pese a su llamamiento del sábado, cuando apeló a la responsabilidad de los legisladores para “evitar la aventura” de las urnas. Ahora el Parlamento será disuelto en un plazo de 10 días a partir de este lunes, para a continuación convocarse elecciones. El primer ministro ha anunciado que los comicios serán el 25 de enero, en la primera de las fechas barajadas. Mediante votación nominal en voz alta, en un agónico goteo de nombres divididos por circunscripciones, los 300 diputados griegos se han pronunciado a favor o en contra del único candidato a la jefatura del Estado, el conservador Stavros Dimas, excomisario europeo y varias veces ministro de Nueva Democracia, el partido del primer ministro Andonis Samarás. Dimas había sido propuesto por el Gobierno (que reúne sólo 155 escaños), y, a diferencia de las dos vueltas anteriores, necesitaba esta vez 180 votos. Ha logrado sólo 168, los mismos que en la segunda votación, el pasado día 23. En sus primeras declaraciones a la salida del Parlamento, Dimas ha manifestado a los periodistas que esperaba este resultado, y ha subrayado que "lo único importante ahora y siempre son los intereses de Grecia, en favor de los cuales todos deben trabajar juntos con sangre fría", la misma, ha asegurado, con que ha recibido el resultado.

Las encuestas apuntan a un triunfo de la izquierdista Syriza, con el 28% de los votos, y a una debacle del bipartito Nueva Democracia —el partido de Samarás— y los socialistas del Pasok, que han ostentado el poder durante cuatro décadas de cómoda alternancia.

La retransmisión en directo de la televisión pública Nerit, con un cintillo en el que podía leerse “elección de presidencia o urnas”, ha sido una sucesión de barridos sobre el hemiciclo con un marcador inscrito en la pantalla, a modo de partido de fútbol, en el que figuraban las dos únicas opciones posibles, Stavros Dimas o “parón” (presente, a modo de voto blanco, la opción de 132 parlamentarios); desde los primeros votos ha quedado claro que era una elección a degüello y que Dimas no sería elegido.

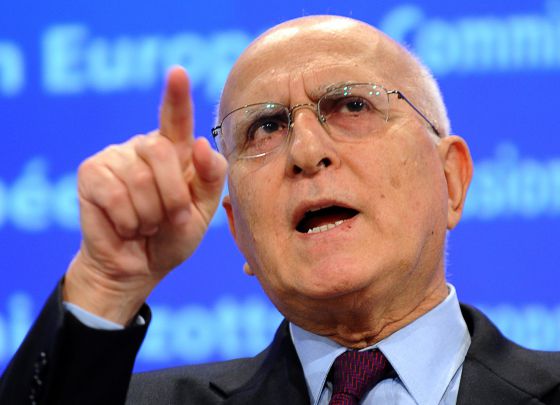

Bruselas ha reaccionado templando gaitas, después del apoyo explícito a Samarás del presidente de la Comisión Europea, Jean-Claude Juncker (que prefiere ver "caras conocidas, no extremistas" en Atenas) y del comisario Pierre Moscovici, que hace apenas dos semanas daba por hecho que el Gobierno griego tendría apoyos suficientes para la elección presidencial. Este lunes se ha comprobado que ese apoyo no existía. Y la cara más probable con la que se topará Juncker a partir de febrero será la de Alexis Tsipras, el líder de Syriza, que encabeza las encuestas.

A mediodía, Moscovici ha lanzado un escueto comunicado en el que la Comisión —el brazo ejecutivo de la UE— manifiesta que es "el pueblo griego" quien debe decidir su propio futuro, y subraya el "fuerte compromiso" de Europa para "el necesario proceso de reformas favorables al crecimiento que será esencial para prosperar de nuevo dentro de la zona euro". Ese dentro de la zona euro está ahora de nuevo en cuestión: los mercados han sacudido duro a Grecia a lo largo de toda la jornada, y los analistas coinciden con Bruselas en que un Gobierno liderado por Tsipras sería negativo para la estabilidad tanto en Grecia como en la eurozona. Pero ni los mercados ni Bruselas votarán el 25 de enero, y lo que Moscovici llama "reformas favorables al crecimiento" han sido ahora varias rondas de dolorosa austeridad que se han llevado por delante casi una cuarta parte del PIB de Grecia, han disparado la deuda pública hasta el entorno del 170% del PIB y, pese a la incipiente mejoría de los últimos meses, mantienen tasas de desempleo dramáticas, en torno al 25%, solo equiparables a las españolas en toda Europa.

domingo, 28 de diciembre de 2014

ARGENTINA: LA ULTIMA ENCUESTA DE 2014

SI HOY FUERAN LAS ELECCIONES, MASSA Y SCIOLI LLEGARIAN AL BALLOTAGE

El líder del Frente Renovador encabeza el sondeo de la consultora González y Valladares. A menos de dos puntos se sitúa el gobernador bonaerense.El estudio arrojó que Macri habría frenado su crecimiento

La última encuesta presidencial de 2014 dejó una foto de la línea de largada para las elecciones 2015: según el estudio realizado por la consultora González y Valladares, Sergio Massa tiene hoy una intención de voto de 29 por ciento; seguido por Daniel Scioli, con 27,1 por ciento, y Mauricio Macri, con 21,2 por ciento.

Eso implica que, si los comicios fueran hoy, el líder del Frente Renovador y el gobernador bonaerense entrarían al balotaje. En esa eventual segunda vuelta, el massismo le sacaría al Frente para la Victoria una ventaja de 9,2 puntos porcentuales. Si Massa se enfrentara a Macri, esa diferencia se ampliaría a 11,6 puntos. Pero si el líder del PRO se midiera con el gobernador bonaerense, este último se impondría por apenas 4,4 puntos porcentuales.

De acuerdo con el estudio publicado por el diario Perfil, entre octubre y diciembre, el jefe de Gobierno porteño habría detenido su crecimiento y cayó 0,3 puntos en intención de voto. En ese período, Massa también sufrió una caída de 0,9 puntos. El único de los tres candidatos con más chances que creció en ese tiempo fue Scioli, que incrementó en un punto su intención de voto, según el estudio telefónico realizado entre 2.400 casos entre el 21 y el 26 de diciembre.

MASSA TIENE UNA INTENCIÓN DE VOTO DE 29 POR CIENTO, SEGUIDO POR SCIOLI (27,1%) Y MACRI (21,2%)

En el cuarto puesto, muy lejos del podio, se ubicó el radical Julio Cobos con 11,3 por ciento. Pero aunque la UCR hoy no parezca tener chances reales de llegar a la Presidencia, González y Valladares evalúa que tendrá un rol clave en los próximos meses: sus votos podrían ser determinantes para inclinar la balanza a favor del massismo o el macrismo para polarizar con el Frente para la Victoria.

Un escenario similar arrojó el sondeo que realizó la consultora Raúl Aragón & Asociados. De acuerdo con su estudio, Massa y Scioli también se enfrentarían en el balotaje. Pero por primera vez la encuestadora relevó que el gobernador bonaerense superó al ex intendente de Tigre por 25,8% a 24,5 por ciento.

Más atrás, con una diferencia que supera el margen de error, Macri se posiciona tercero con una intención de voto de 20,4 por ciento.

Pero si el escenario incluyera a todos los candidatos que hoy se anotan para las primarias, las posiciones varían radicalmente. Según González y Valladares, el Frente para la Victoria acumula para las PASO una intención de voto de 29,8 por ciento, conformada por el 12,8% de Scioli; el 8,6% del ministro de Interior y Transporte, Florencio Randazzo; el 2,9% del ministro de Economía, Axel Kicillof; el 2% del flamante secretario general de la Presidencia, Aníbal Fernández; el 1,3% del gobernador entrerriano Sergio Urribarri y porcentajes menores del resto de los postulantes.

Pero aunque el kirchnerismo se ubique primero en las primarias, esa intención de voto lo dejaría en el tercer puesto a nivel de candidatos, superado por Massa y Macri. Un escenario similar registró Raúl Aragón & Asociados: en las primarias, Scioli se ubicaría tercero con 16,74 por ciento por el 7,31% que cosecha Florencio Randazzo. Pero, según el relevamiento, el gobernador bonaerense podría volver a entrar en el balotaje en las elecciones generales.

Pero aunque el kirchnerismo se ubique primero en las primarias, esa intención de voto lo dejaría en el tercer puesto a nivel de candidatos, superado por Massa y Macri. Un escenario similar registró Raúl Aragón & Asociados: en las primarias, Scioli se ubicaría tercero con 16,74 por ciento por el 7,31% que cosecha Florencio Randazzo. Pero, según el relevamiento, el gobernador bonaerense podría volver a entrar en el balotaje en las elecciones generales.

sábado, 27 de diciembre de 2014

EL CASO SONY-COREA DEL NORTE Y LA AUTOCENSURA EN OCCIDENTE

De las caricaturas de Mahoma a la del Brillante Camarada

El debate sobre los límites de la libertad de expresión salta a la cultura popular

MARC BASSETS Washington DIARIO EL PAIS, MADRID27 DIC 2014

El estreno, el día de Navidad, de The interview (La entrevista), la sátira del dictador norcoreano Kim Jong-un, se ha celebrado comoun triunfo de la libertad de expresión, un desafío a la amenaza de represalias por ofender al llamado Brillante Camarada. La película, una comedia de sal gorda protagonizada por Seth Rogen y James Franco, se estrenó en unos 300 cines alternativos por todo Estados Unidos y puede descargarse en Internet. En su primer día hizo una taquilla de un millón de dólares, según Sony Pictures.

En los días que EE UU normalizaba las relaciones con Cuba, uno de los vestigios de la Guerra Fría, el incidente con Sony recuerda al mundo que en Asia la Guerra Fría sigue viva. Los ataques informáticos contra la multinacional también recuerdan que, en la era de la ciberguerra —o el “cibervandalismo”, como lo definió el presidente Barack Obama—, la primera potencia y su industria más universal, Hollywood, son vulnerables.

El debate sobre los límites de la libertad de expresión no es nuevo. Ahora llega a Hollywood y a la cultura popular. La fetua del imán Jomeini en 1988 contra el escritor Salman Rushdie por su novela Los versos satánicos fue uno de los primeros casos con ecos globales de intimidación por una supuesta ofensa religiosa. En 2005, la publicación en el diario danés Jyllands Posten de unas caricaturas de Mahoma desató protestas en países de mayoría musulmana y abrió una discusión: ¿deben los medios, los artistas, abstenerse de ofender a colectivos o personas para evitar represalias?

Las diferencias entre las caricaturas de Mahoma en el Jyllands Posten y la caricatura de Kim en La entrevista van desde el objetivo de la sátira a la reacción de los ofendidos. En 2005, el objetivo era el islamismo violento. Y el contexto era el de una Europa con minorías musulmanas y episodios de tensión con la mayoría autóctona.

Esta vez es distinto. El objetivo de la sátira es un autócrata en un país lejano, sin conexiones culturales con el mundo desarrollado. No hay comunidades norcoreanas en EE UU y Europa. El miedo de quienes esta semana estrenaron la película no era tanto a atentados como a ciberataques como los que en las últimas semanas ha sufrido Sony.

Flemming Rose acaba de publicar en EE UU The tyranny of silence (La tiranía del silencio), un ensayo sobre los límites a la libertad de expresión en los países occidentales. Rose fue el responsable, como jefe de Cultura del Jyllands Posten, de la publicación de las caricaturas de Mahoma. Desaprueba la decisión de Sony, la semana pasada, de retirar la película, decisión corregida parcialmente al estrenarse ahora en los 300 cines independientes y en Internet.

“Puedes decir que Sony es una corporación de entretenimiento y están en el negocio para hacer dinero. Por tanto, deben decidir en función del negocio, y no de acuerdo con su responsabilidad ante el público como un medio de comunicación que se ve a sí mismo como una institución que defiende un bien público”, dice Rose en una entrevista por teléfono. Pero añade: “Sin la libertad de expresión Sony no sería capaz de hacer muchas de las películas que está haciendo. Si operase en un ámbito como el de Corea del Norte, diría que quizá el 90% de sus películas no podrían producirse. Así que desde un punto de vista del negocio Sony también se beneficia de la libertad de expresión”.

Que finalmente Sony haya difundido La entrevista es digno de aplauso, según Rose. Demuestra, en su opinión, que la realidad de la globalización impide calcular los efectos. Lo que apaciguaría al líder de Corea del Norte —retirar la película de circulación— merece los reproches del presidente de EE UU y puede perjudicar a la multinacional en el mercado norteamericano.

Después de publicarse las caricaturas de Mahoma, el discurso de la mayoría de líderes europeos y del entonces presidente de EE UU, George W. Bush, fue ambiguo: defendieron la libertad de prensa pero resaltaron las responsabilidades que esa libertad conlleva. El periodista danés recuerda que, como ahora, las amenazas no resultaron efectivas del todo. “Diría que en un 60% de países europeos hubo grandes diarios que republicaron las caricaturas”, recuerda.

Rose no es optimista. Ve una tendencia hacia la autocensura incluso en EE UU, donde la Primera Enmienda garantiza la prevalencia de la libertad de prensa. “Me preocupa lo que ocurre en los campus de Estados Unidos y Reino Unido”, dice. Menciona los debates, en universidades norteamericanas, sobre la necesidad de alertar a los alumnos de que obras como El gran Gatsby o Las aventuras de Huckleberry Finn contienen pasajes que algunos alumnos pueden considerar misóginos o racistas y, por tanto, ofensivos.

Rose sostiene en su libro que en una democracia no debería existir el derecho a no ser ofendido. “Cuando celebras la diversidad cultural y religiosa, también debes celebrar la diversidad a la hora de expresarte”, dice. “Pero vamos en sentido contrario. Queremos tener más diversidad cultural pero al mismo tiempo tendremos menos diversidad de expresión. Cuando [el cineasta holandés] Theo Van Gogh fue asesinado, el ministro de Cultura de Holanda dijo que si las leyes sobre los discursos del odio hubiesen sido más duras y las obras de Van Gogh se hubieran prohibido, seguiría vivo”.

El triunfo de la libertad de expresión en el caso de la sátira sobre el dictador norcoreano ha sido a medias. Las amenazas no han impedido que quien lo desee pueda ver la película en EE UU, en salas u online. Pero los 3.000 cines comerciales que debían estrenar La entrevista no lo han hecho. En el futuro, antes de invertir en un proyecto que pueda ofender a un político o un colectivo se lo pensarán.

Vetado el filme ‘Exodus’

Las autoridades de Egipto y Marruecos han prohibido el estreno de la película Exodus: dioses y reyes, dirigida por Ridley Scott y protagonizada por Christian Bale. El filme narra la rebelión del profeta Moisés frente al faraón Ramsés y la liberación de centenares de miles de esclavos judíos. El Gobierno egipcio ha justificado su decisión por el hecho de que la producción de Hollywood contiene “falacias históricas”. En concreto, la Oficina de la Censura ha criticado el hecho de que se muestre a los esclavos judíos construyendo las pirámides y la gran esfinge, pues sus responsables aseguran que está probado que éstas fueron erigidas siglos antes. Asimismo, ha censurado que las aguas del mar Rojo se abran ante Moisés —también un profeta para el islam— tras un terremoto, poniendo en duda que fuera un milagro divino.

La proyección del filme en Marruecos fue prohibida unas horas antes de su estreno el 24 de diciembre, según la revista Tel Quel. El responsable de un cine de Casablanca declaró a la publicación haber recibido “amenazas” del Centro Cinematográfico Marroquí (CCM). La decisión fue acogida con sorpresa por los distribuidores, pues contaban con todos los permisos. No obstante, según la agencia Efe, la película ya se puede encontrar en el mercado negro. La producción del filme contó con un presupuesto de 115 millones de euros y se estrenó en España el 5 de diciembre.

FRANCIS FUKUYAMA, CHINA AND THE END OF HISTORY

Francis Fukuyama: ‘In recently democratised countries I’m still a rock star’

The world-renowned political thinker on what’s left of ‘The End of History’, the crimes of the neocons and having the ear of the Chinese leadership

THE GUARDIAN

The first volume of Francis Fukuyama’s history of political development has been one of only a handful of books by a foreigner to make a profit in China. As Fukuyama explains when we meet near his home in Palo Alto, California, foreign books in China are usually pirated. But The Origins of Political Order, which narrates the emergence and growth of the state “From Pre-Human Times to the French Revolution”, engages respectfully with Chinese history and culture, and features an overarching version of national history that the Chinese themselves no longer teach or learn. Enough of his account of the country’s enormous historic strengths and equally enormous historic weaknesses survived the censor’s scalpel to make the work valuable to the Chinese reading public.

Fukuyama goes on to say that a friend in Beijing had learned that the Communist party would translate that book’s recently published companion volume, Political Order and Political Decay for publication in a private edition for its senior leadership. “They take the analysis seriously,” he said. The two volumes set out to compare and contrast the progression of various societies across time, in pursuit of a goal he calls “Getting to Denmark”. The proverbial Denmark, like the actual state, is a robust liberal democracy with an effective state constrained by the rule of law – a package “so powerful, legitimate, and favourable to economic growth that it became a model to be applied throughout the world”.

As he describes his reception in China, Fukuyama beams with pride that the authorities regard him as sufficiently impartial to take notice of, especially as he is perhaps the person most closely identified with the espousal of the victory of western liberal democracy over all its ideological competitors. Fukuyama became an unlikely intellectual celebrity back in 1989 when he declared that the defeat of the USSR in the cold war represented not “the passing of a particular period of postwar history, but the end of history as such: that is, the end point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalisation of western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.” To have written a book 25 years later that the Communist party elite in Beijing feels compelled to make compulsory reading is a feat plainly gratifying to its author and ensures that his stern and chastening message will have been received by at least one of the audiences to whom it is addressed.

His book makes clear the fundamental debility of a political system lacking upward accountability, as the still nominally communist Chinese system does. But it also emphasises the dangers of the improper sequencing of different elements of political development: too much rule of law too soon can constrain the development of an effective state, as happened in India; electoral democracy introduced in the absence of an autonomous administrative bureaucracy can lead to clientelism and pervasive corruption, as happened in Greece. Even the societies in which a proper balance of democracy, rule of law and an effective state has been struck in the past are susceptible to political decay when rent-seeking extractive elite coalitions capture the state, as has happened in the US. The failure of democratic institutions to function properly can delegitimise democracy itself and lead to authoritarian reaction, as happened in the former Soviet Union.

“They understand that their system needs fundamental political reform,” Fukuyama says of the Chinese. “But they don’t know how far they can go. They won’t do what Gorbachev did, which was take the lid off and see what happens. But whether it will be possible to spread a rule of law to constrain state power at a pace that will satisfy the growing demands of the rising middle class is also unclear. There are 300 to 400 million Chinese in the middle class; that number will rise to 600 million in a decade. I had a debate a few years ago with an apologist for the regime. I pointed out that in many regions of the world when you develop a sufficiently large middle class, the pressure for increased political participation becomes irresistible. And the big question for China is whether there will be a point at which its people will push for greater participation, and he said: ‘No, we’re just culturally different.’”

It was, in effect, a rehash of the old “Asian values” argument concerning the hierarchical and deferential social ethic that goes by the name ofConfucianism in east Asia – allegedly the reason that Asians lacked the impulse to individual self-assertion that resulted in the demand for self-government in other parts of the world. The democratic transitions in South Korea and Indonesia put an end to that argument decades ago, Fukuyama says, just as the Arab spring debunked a parallel claim regarding Arabs. This is the part of Fukuyama’s argument about the end of history that he still stands behind without reservation or qualification – the Hegelian philosophical anthropology that saw history as the working out of the struggle between masters and slaves for recognition. “I really believe that the desire for recognition of one’s dignity and worth is a human characteristic. You can see manifestations of this in all aspects of human behaviour cross-culturally and through time.”

Advertisement

The relevant historical analogue for the Chinese rulers, Fukuyama says, is probably Prussia under a series of enlightened monarchs, which allowed a rule of law to spread gradually without extending democratic participation to the people. But, of course, Germany came to the “end of history” after initiating and fighting two of the most brutal wars the world had ever seen.

Would the next rising power be able to control the titanic energies of its people and manage a transition that avoids the blood-letting Europeans had to endure?Political Order and Political Decay emphasises the enormous difficulty of implanting democratic political institutions in places where the state has collapsed, or where it never really took root in the first place. For Fukuyama, the great challenge of state-building is creating and sustaining an institution of collective rule that cuts against the grain of human nature: we are designed to favour friends and family, and a patrimonial tribal order is “hard-wired”, he argues, into our neural circuitry. Though the right set of institutions can allow us to override these instincts, we naturally revert to them whenever political order breaks down. The first volume of his book recounts the expedients to which the first modern states resorted to overcome tribalism – it discusses the eunuchs who administered the Chinese state, the kidnapped Christian slaves who ran the Egyptian state – and the historical accidents that allowed state, society and rule of law to reach an equilibrium favourable to modern political order in western Europe. The second volume demonstrates how vulnerable even the best-developed modern state apparatus is to “repatrimonialisation”. Both volumes emphasise that the state is an institution that feeds on war, one whose national stability has often been buttressed by ethnic cleansing; and that the European Union after 1945, for instance, was built atop a pile of mass graves.

In some ways, Fukuyama says, he has been “trapped” by the ideological cul-de-sac in which his claims regarding the “End of History” have placed him. Though he still stands behind the assertion that liberal democracy is the eventual destination of history, he has qualified his argument and narrowed the scope of his ideological triumphalism, postponing the arrival of liberal democracy to the indefinite “long run”. He would not, he tells me, use the same heightened rhetoric today that he used in 1989 to describe what he now calls a “historically contingent demand for greater political participation” that ensues as people become more prosperous and educated.

Fukuyama’s career as a public intellectual began with an essay that promised to distinguish between “what is essential and what is contingent or accidental in world history”. His own career, as he makes clear to me, was almost entirely a series of accidents. He took up ancient Greek under the influence of his charismatic freshman year teacher Allan Bloom, who inculcated him into the ideas of the emigre German philosopher Leo Strauss, and to a network of aspiring young intellectuals that included men who would figure prominently in his later career, Paul Wolfowitz and I Lewis “Scooter” Libby. There was a detour into the modish French philosophers of the day, as part of which he made a pilgrimage to Paris (where he also wrote a novel) to study with Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacanand Roland Barthes. But he soon concluded, while enduring an interminable session in which Barthes would riff, pun and free associate over random sequences of words pulled from the dictionary, that “this was total bullshit, and why was I wasting my time doing it?”

He applied to Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government to study national security. While the French post-structuralists and their epigones would go on to dominate American literature departments in the 1980s, his new cohort at the Kennedy School would populate the State Department and Pentagon. And in a remarkable turn of events, Fukuyama’s old mentor Bloom would become a bestselling intellectual celebrity with The Closing of the American Mind, two years before Fukuyama’s own ascent to global fame.

“The End of History?” began as something of a recondite joke. Fukuyama was at the time a mid-level figure in the Reagan State Department witnessing the rapid unravelling of the Soviet mystique. “I remember there was a moment when Gorbachev said that the essence of communism was competition, and that’s when I picked up the phone, called my friend and said, ‘If he’s saying that, then it’s the end of history.’” Fukuyama is careful to point out that the coinage was not of his own making, but instead that of a Russian émigré professor named Alexander Kojève whose seminars on Hegel influenced postwar French existentialism.

But the triumphal eulogist of America at its world historical apogee never fell victim to the crude simplification of his own argument to which his neoconservative friends fell prey – and which his own rhetoric had done so much to invite. As he would later write in a 2006 book repudiating the neoconservativism of his youth, the misreading of the events of the 1989 led directly to the calamities of the early 21st century that, in his view, have forever discredited the neocon approach to the world. “There was a fundamental misreading of that event and an ensuing belief that if America just did what Reagan had done, and stood firm, and boosted military spending, and used American hard power to stand up to the bad people of the world, we could expect the same moral collapse of our enemies in all instances.” Fukuyama continues to credit Bloom and Strauss with broadening his intellectual horizons, but the adventure the adherents of those neocon thinkers embarked on, culminating in armed intervention in Baghdad, was, Fukuyama says, a bloody fiasco. “I don’t know how they can live with the consequences of their actions.”

Fukuyama has always been an intellectual comfortable with his proximity to power, conceiving of his role as offering guidance to the organs of the American national security state, starting with his first job at the Rand corporation in the late 1970s. He has never indulged the romance of the adversary intellectual who sees the working of that system as irremediably corrupted. He showed me the cover of a recent issue of Foreign Affairs carrying an excerpt of Political Order and Political Decay whose headline announces “America in Decay”, and indicated his discomfort with broadcasting a message that would give comfort to America’s geopolitical adversaries.

It is one index of the state of American politics when a man of such impeccably centrist instincts feels impelled to assert, as Fukuyama has done, that the US has become an oligarchy, and to lament the absence of a leftwing popular movement able to check the excesses of that oligarchy. He insists that he was right in the 1970s and 1980s to oppose the expansion of the welfare state, and to support the muscular use of American power around the globe during a time of retrenchment. But the pendulum has swung far in the other direction. “What I don’t understand is my friends on the right who don’t think it’s necessary to rethink their ideas in light of subsequent events.”

“I think where I’ve had my biggest and most positive audience is in recently democratised countries – Ukraine, Poland, Burma and Indonesia,” he says. “In places like that, I’m still a rock star. In places like that, the End of History writings allowed people to see themselves as a broad historical movement. It wasn’t just their local little disputes, there were deeper principles involved. And to be able to go to those places and tell them that they are on the right side of history with regard to political change – to this day I’m touched by it. To be able to go to Kiev and tell people there that democracy still remains the wave of the future – it’s in those moments that I feel most fully that I’ve made and am making a lasting contribution.”

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)